For some reason I’ve always had a thing for Lawrie bagpipes. Recall, I purchased African blackwood Lawries that turned out to be cocus wood Hendersons: not a bad trade-off as most will agree! I love this vintage set of ivory-mounted Hendersons, the look is pure old school, and the tone is ethereal; they are a real delight to play. However, I have also had a thing for wood-mounted pipes and, with a desire to give some Lawries a try, the planets recently aligned on both counts. A set of early ebony and nickel Lawries in the UK in apparently very good condition came across my radar. With ivory bushes and a marked jR.G. Lawrie Regal ivory-mounted chanter, these pipes fall within the realm of CITES I Appendix materials. In this new era of CITES Appendix and IUCN Red Listed materials, exportation and importation of bagpipes with ivory, African blackwood, Gaboon ebony, cocus wood, and other materials has become more complex. So, with worked African elephant ivory and Gaboon ebony these pipes required paperwork.

Most of us know very little about the process of exporting or importing objects on the CITES I / II Appendix or IUCN Red List. Bagpipes that used to be freely traded across the world are now subject to Export and Import permits, in addition to statements verifying the materials, in order to complete the transaction. Ron Bowen has an excellent treatise on importing bagpipes with ivory that fall under the CITES I Appendix into Canada and the US. However, this doesn’t (yet) cover wood, and the majority of bagpipes being sold across border these days are made of wood that is CITES I Appendix listed. For more info on wood and CITES and other designations, check out my Bagpipe Woods page. Note, that Ron can usually provide verification of the make , date of manufacture, and wood type of your bagpipe with his Certificate of Authenticity (COA), and often from photographs. I have had two of these COAs done by Ron with fantastic results. While I have only used the certificates for identification, valuation, and insurance purposes, I believe that this COA would be invaluable in providing an assessment of the materials for an Export Permit in whatever country you live (see below for more details).

As I am in Canada and attempting to purchase a set of early ebony and ivory Lawries from the UK, I’m going to provide some information on the export and import of these pipes as the process unfolds. Some of the steps may well be transferable between other countries, but I am only guessing; despite extensive research and conversations about the process of moving pipes between the UK and Canada the steps are still not entirely clear. First a little bit about the pipes themselves…

The Main Character: 1913 – 1920 (WWI) Ebony, Nickel, and Ivory Lawries

The story of these vintage ebony Lawrie bagpipes with nickel ferrules and ivory bushes, and chanter with a large ivory sole is interesting and, in a way, begins with a girls pipe band in 1920. Thus, the history of these pipes can be fairly reliably traced back to at least that date, and likely a few years earlier. But more on this later. Let’s start with a few images of what are very probably an ex-military set of Lawries turned sometime between 1913 and 1920 (WWI-era):

Bagpipes were a common military issue instrument through WWI, into WWII, and even afterwards, to a lesser degree. Pipers would be trained in the military and given a set of pipes, often assembled from a box of parts in stores. The pipes would stay with the piper until they were discharged and the pipes went back into stores. I have seen images of sets of pipes with serial numbers engraved into the (ivory) drone caps, ferrules, or even somewhere on the drones. One mark that appears to repeat itself is the crow’s foot or more properly, a broad arrow, and sometimes a year is inscribed. Apparently, the broad arrow was stamped onto military equipment to prevent theft! But this is just a diversion; as far as I know, most military bagpipes were unmarked, including the set I am looking at. Here’s the broad arrow on a set of 60s or 70s R.G. Hardies:

African blackwood R.G. Hardie bagpipe with catalin mounts and caps. Hardie and the broad arrow are marked in the cord groove of a tenor drone. It should be noted that marked Hardies are almost as rare a hen’s teeth! More on that on the Henderson vs. Lawrie vs. Hardie. page.

At some point military pipes, marked or unmarked, would be given to discharged pipers or considered surplus and sold off by the military to the general public, sometimes in lots. If one can track these transactions one may have a means of determining the age of the instrument.

Based on information from the seller and my own research, the Victoria Street Girls Pipe Band formed in Willenhall, England in 1920, obtaining their pipes and uniforms (and probably drums) as military surplus. Many of the sets of pipes purchased by Victoria Street were wood-mounted Lawries and Hendersons, among others, some full-mounted, others button-mounted, some flat-combed, others beaded and combed. Of course, military sets were often wood-mounted and flat-combed, likely to keep the price down but not necessarily all called Military sets. For example, in the earliest Peter Henderson catalogs (pre 1930) it looks like military bagpipes is in reference to full size sets, viz-a-vis, “the great highland or military bagpipe”; the other categories, No. 2, 3, and 4 are smaller versions. The 1930 catalogue lists all sized sets under the section title Great Highland or Military Bagpipes. However, military, at least in Peter Henderson’s world, likely just means, the big pipes!

In the catalogues I have had access to in Jeannie Campbell’s excellent books and elsewhere, wood-mounted pipes are not directly referred to until 1969. For the ’88, ’90, and ’05 Henderson catalogues, the first category under No.1 is 1. which, as mentioned, is listed as The Great Highland or Military Bagpipe, made of Ebony or Cocoa Wood, full mounted with ivory. The prices then follow at £7, £8, £9, and £10. So, you can get a full-mounted ivory set for £7, but what the heck do you get for the three price-points above that? Where do wood-mounted sets fit within this realm? Or were they even available then? Perhaps the four prices refer to a combination of wood type (ebony or cocus wood, and/or the chanter material and/or sole, or other things added). African blackwood is listed as a separate upgrade of £1 in 1930, and probably earlier.

I can’t find any direct listing of wood-mounted types in Peter Henderson catalogues until 1969 (but that’s likely due to lack of samples to review). I find it hard to believe, but maybe Henderson didn’t turn out any wood-mounted sets until the teens; though some Henderson wood-mounted sets have ivory ring caps and bushes, many more have casein (teens – 20s) or catalin (30s +) tops. As a comparison, some of the earliest wood-mounted Lawries can be dated to 1912 or perhaps a little earlier, based on the straight-sided and scribe-lined ferrules, use of celluloid, and overall profile. I can’t seem to find any R.G. Lawrie price lists for bagpipes, only the one you posted a while ago on sporrans, etc.

Thus, in a way, Henderson and Lawrie wood-mounted bagpipes could well be a later addition to their lines. I wonder if the lower price for wood-mounted sets and less ivory used was targeted at the military, and we certainly have seen evidence of this.

Wood-Mount Styles and Possible Associations to Date of Manufacture

Knowing when these pipes were sold as surplus, i.e., 1920, we can assume that these ex-military bagpipes would have likely been manufactured in the teens and possibly earlier. I’m going to take a little diversion here. There are two, three, perhaps even four generations of wood mounts on Lawries and there ‘may’ be a connection with date of manufacture. Hendersons are a little bit of a different story. For more information please see my identifying Lawries and Hendersons by Wood Mounts page. Safe to say, these pipes are Generation I.b wood mounts:

As a point of comparison, here are the three wood mount styles:

Three generations of Lawrie wood mount styles. First set of images from Gord MacDonald at Island Bagpipes. Set two is mine, and three from Jim McGillivray’s Vintage Bagpipes page. Note, the similarities among Generation I mounts. The I.a style appears to be quite rare and associated with scribe-lined ferrules.

Something else to consider are the ferrules. Lawrie closed and beaded ferrules lost their scribe lines and became progressively more tapered after around 1910. Given the history of my Lawries, and the fact they have slightly tapered ferrules, I would place the date of manufacture sometime between 1913 and 1919. I don’t believe that the date can be extended any later than 1919 given the pipes were sold as surplus in 1920; one would assume that newer pipes would be retained by the military. That said, Jim McGillivray has sold a set identical to these that he suggests could have been turned in 1930, so who knows about my suggested classification system. More on that on my Hendersons vs. Lawries. vs. Hardies page.

This particular set of Lawries is surprisingly intact, with all parts more or less matching; one tenor is has slightly different beading and a different bore but essentially matches the other drone tops. In fact, it is quite common to find mismatched parts even with a bagpipe that is still intact from the shop to present — check out the slightly off beading and combing spacing on my WWI Hendersons and dozens of other Lawries and Hendersons out there. What can likely be said with some degree of confidence is that the parts were likely turned close to the same time, maybe by the same turner, given the consistency. But, of course, tone trumps all, and this set of early Lawries is bold and harmonic but refined tone, typical of many vintage ebony Lawrie or Henderson bagpipes.

Sister Sets of Pipes

Recall, that many of the sets sold to the Victoria Street Pipes and Drums were likely made around the same time. The seller of these indicated that he has a number of identical matching sets. Here are some images of one of the ‘sister’ sets of Lawries to those I am attempting to purchase. They are in a little rougher condition but virtually identical to the above set:

Victoria Street Girls Pipe Band: ~1920 – 2000

As noted above, the story behind these ebony wood-mounted Lawries figures prominently in Willenhall, England, near Birmingham. The Victoria Street Girl’s Pipe Band formed there shortly after WWI, obtaining their pipes and uniforms as military surplus. The band was eventually made up of women and men, though any available images appear to only include girls. The band played around the UK, internationally, and were apparently featured on television before they disbanded in 2000. At that time at least 15 sets of the ex-military sets were sold off to one individual/band, and were subsequently played by band members and individuals in the Scottish Piping Society, or were stored. As the band members retired and sets came back, the owner of these sets decided to sell some of them. And that’s how we have come to this point.

The following are a number of images of the Victoria Streets Girls Pipe Band from the 1970s marching in the Darlaston Carnival. Check out the pipes these gals are playing: they appear to be similar, if not the same pipes as depicted above! Well, who knows, but now you see the connection. Of course, these cannot be the original ex-military uniforms but the band is turned out quite nicely (though, those cords and bass drone need a little attention!).

Victoria Street Pipe Band marching in the Darlaston Carnival around 1976. The pipes this gal is playing are very likely one of the ex-military ebony Lawries discussed above. Image from http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/DarlastonCarnival/Carnival.htm

Those sure look like wood-mounted Lawries to me. Darlaston Carnival, 1976ish. http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/DarlastonSlides/Album.htm

Piper from the Victoria Street Girls Pipe Band playing a catalin-mounted set of pipes – 1976 – Darlastan – carnivalFrom: http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/DarlastonSlides/Album.htm

Victoria Street Girls Pipe Band marching in the Darlaston Carninval in the 1970s. They may well be playing the ex-military pipes obtained when the band formed in 1920. Image from: http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/DarlastonCarnival/Carnival.htm

Victoria Street Girls Pipe Band marching in the Darlaston Carninval in the 1970s. Image from: http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/articles/DarlastonCarnival/Carnival.htm

Apparently, the name of the pipe band was changed to, or known as, The Victoria Street Willenhall Girls Pipe Band. I am in contact with some ex-members of this band, including someone in these images, and hope to get more information on the band in the future.

A Saga of Importing a Set of Bagpipes from the UK to Canada

Of course, the story has not yet finished. What’s needed is an explanation of the process of exporting and importing a set of pipes. That’s right, exporting. As purchasers of bagpipes we are generally only concerned with Import permits, but that is only half of it. Before a set of pipes can be imported into a country, they have to be exported from another. Both of those permits have to link up at some point. It’s a good idea for both parties to work with each other to facilitate the process.

The seller of the Lawries navigated this process from both sides of the Atlantic. Not wanting to leave any stone unturned, I have also been in contact with the Canadian Government on Importing bagpipes and the UK Government on Exporting bagpipes. To add, I’ve been in contact with a reputable seller in the UK for some info on the process. From all of these sources I am finally getting an idea on what is required by the seller and the buyer. However, as I note below, the trade of musical instruments made with materials under the CITES I and II Appendices is relatively new and a moving target, Recall that African blackwood only made the CITES II Appendix in January 2017. Thus, what I report here may or may not apply in every case, particularly outside of UK – Canada transactions. Transactions between the US and UK and Canada and US may require different processes. Additionally, what works right now may not work in the future.

For the present transaction of purchasing a CITES I Appendix bagpipe from the UK and importing it into Canada, as I have found out, at least in Canada, the assessment/verification of the materials in the bagpipe (something that Ron Bowen could provide with his Certificate of Authenticity) is generally only required for the Export Permit; the officials at the Canada CITES office assessing your application for an Import Permit for those same bagpipes defer to those issuing the Export Permit for verification of the materials. In my case, the seller in the UK has had to provide verification of the materials to the UK CITES management office in order to obtain his Export Permit. I have this in writing from the Canada CITES people, including the fact that photographs are not required for the Import Permit, even though the permit needs to be issued before the pipes can be brought into the country!

The Canadian CITES folk do strongly suggest that the Import Permit in Canada can be expedited, at least from an assessment perspective, by having a good digital copy of the Export Permit from the UK included with the application. In my situation, the Export Permit has been applied for and amended, as the initial application did not have the correct information from the seller. It seems that while Gaboon ebony is on the CITES II Appendix, worked ebony is not covered; in this case it only appears that the ivory is an issue and it turns out that it’s a CITES I material. Thus, these permits can be quite confusing if you have not filled one out before. Specifically, the form (Import in Canada and Export in the UK) includes boxes for raw and unworked versions of the CITES I and II Appendix Materials — in this case, Gaboon ebony and African elephant tusk — and it’s not always clear where these are to be listed. If in doubt, choose the more stringent classification, CITES I.

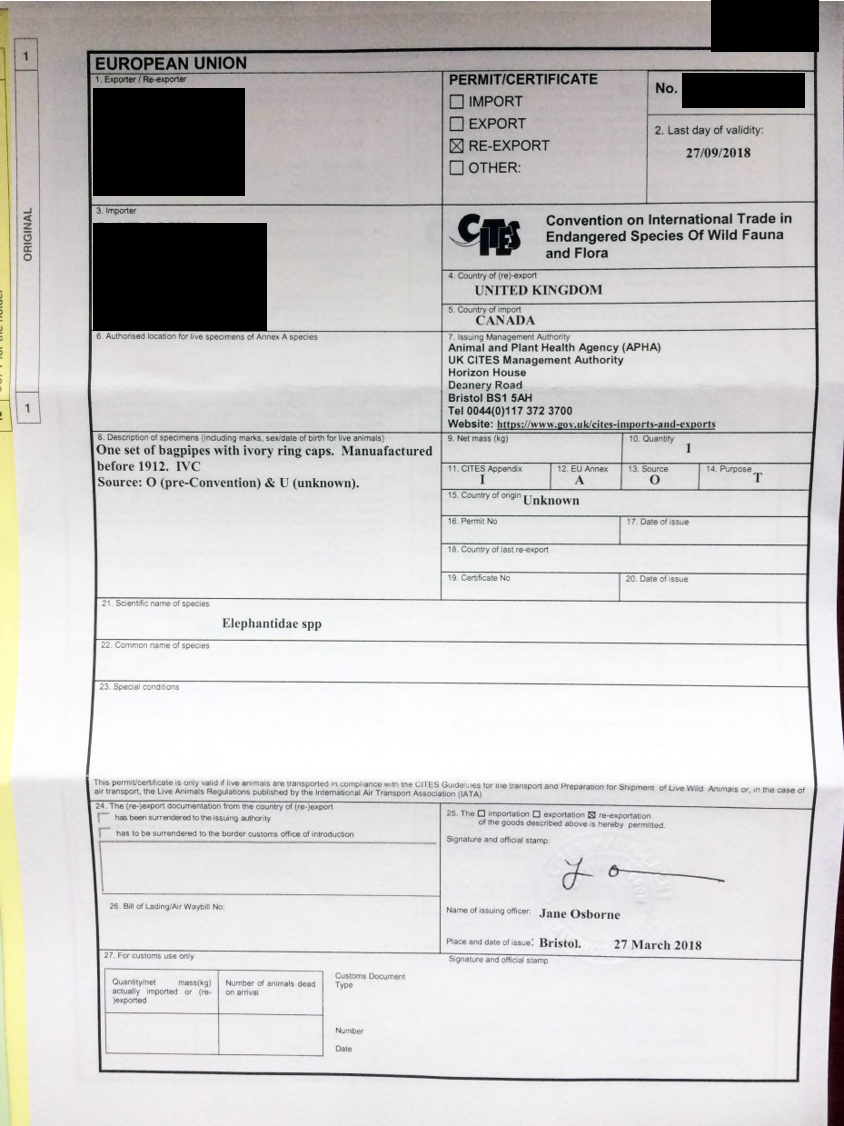

As of March 27, 2018, the UK CITES Export Permit was issued! I applied for an Import Permit here in Canada. Here is what the issued EU (UK) Re-Export permit looks like:

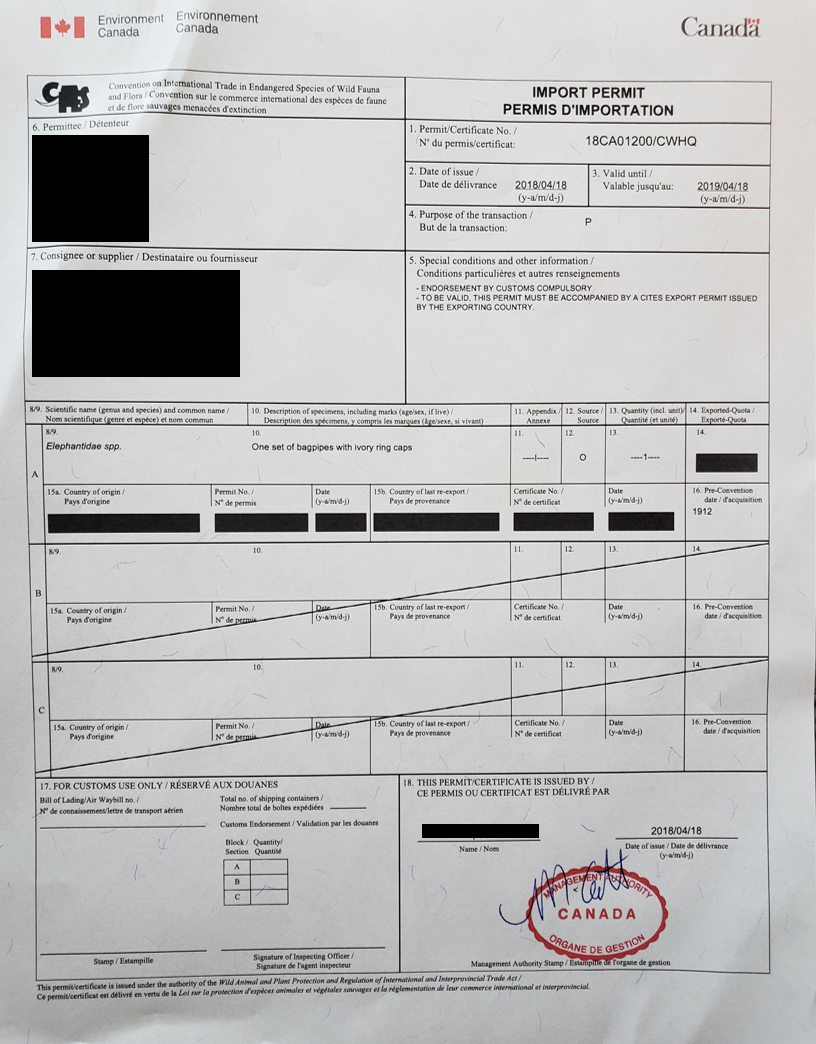

In the meantime, I instructed the seller to ship the pipes; they arrived literally in about 30 hours by expedited shipping; Canada customs processed them with the appropriate duty. At the time I received my pipes my CITES Import Permit application had not yet been processed. When I discussed this with the Canadian CITES officials they were very understanding and for this one occasion have issued the Import Permit, under condition that if I import pipes again I wait for the Import permit to be issued. Here is what an issued Canadian CITES Import Permit looks like:

Canadian CITES IMPORT PERMIT. This permit is required in tandem with, in this case, the UK Export permit, in order for the pipes to be legally brought into Canada.

With all of this in mind…

Here are some short instructions on how to purchase a set of CITES I or II Appendix bagpipes from the UK if you live in Canada:

Instructions on How to Import a Set of CITES I – II Appendix Bagpipes into Canada from the UK!

In my conversations with Canadian and UK CITES officials it became clear that the whole process is relatively new for musical instruments and each of the departments appear to be in learning curve. Thus, each transaction may differ. Here is, step-by-step, what I recommend at this point in time:

- Find a cool set of bagpipes with ivory and some rare wood like ebony or cocus wood for sale in the UK! Make sure you live in Canada, eh!

- Ensure the seller gets A) a recognized assessment of the materials in the bagpipes, be they ivory, or ebony, etc., and B) with this recognized assessment, applies for a UK CITES Export Permit. Note, that while this is an Export Permit, because the ivory on the pipes was imported into the UK ~1910 it is now a Re-Export classification. Here is the schedule of fees for Exporting from (and Importing to the ) UK. In this case the Re-Export certificate is required and the cost is £37 (~$65 Canadian), something you would have to work out with the seller. I am of the volition that the seller should be responsible for these fees as there will be plenty of fees on our end to look after. Note, worked Gaboon ebony is apparently excluded from CITES. The seller just needs to state this in the application or it may get stalled. The UK CITES folk have told me that there is a 14 day turn around for correctly filled out UK CITES Export permit applications. Here is the link to the the CITES UK information; you may need to send that to the seller! As you can see from the above, worked ivory for export (or re-export in this case) is listed under CITES I, not CITES II as I have been led to believe. An acquaintance who works for the National Museum in Ottawa strongly suggested to me that I apply for the Canadian Import Permit using CITES I for the ivory.

- Instruct the seller to email you a good digital copy of the issued UK CITES (Re-) Export permit for those bagpipes. You will need this to expedite your application for a Canadian CITES Import permit. Note, at the time I was discussing this with a Canadian official there was no certainty on whether to instruct the seller the hold on to the bagpipes until I receive my Import Permit or to have the seller ship the pipes as soon as possible. The turnaround time for a Canadian CITES Import applications is officially 35 business days. However, it turned out to be about a third of that, close to the U.K. turnaround time of officially 14 days. In our case, one of the reasons the UK Export Permit took over six weeks is that the CITES office was being moved. It should be noted that there is a six-month validation expiration date with the Re-Export Permit; in my case it is September 27, 2018. Thus, it’s better to err on the side of caution and get the ball rolling sooner than later to get everything completed within that time frame.

- Fill out a Canadian CITES Import permit (Form A1) application found here. Note that this CITES Form A1 is meant to be a catch-all document. There will be categories that do not make sense. Much of the form refers to live specimens. You may not know who or if there is a broker, let alone a contact name and address, or which Canadian port of entry your bagpipes will arrive. I have been instructed to leave these categories blank by the Canadian CITES folk. I mentioned to the CITES contact that I will put N/A or something descriptive in these blanks to ensure they know I did not overlook anything. There is no cost for this permit unless you want to include a pre-paid envelope or courier account number for expedited service.

- Send your completed CITES Form A1 application form (Canadian CITES Import permit) WITH a copy of the UK CITES Export permit by email to cites@ec.gc.ca. You can send it by regular post or courier, if you wish. Note, that upon receipt of the application the process could take a while; as noted above, the Canadian CITES folk have told me that there is a 35 business day turn around for correctly filled out Canadian CITES Import permit applications! You will want to take this into consideration. As noted above, the process took around 10 days — I was pleasantly surprised.

- Wait. Perhaps as much as six weeks but maybe much less. As I have now confirmed, you will need the Export and the Import permits before you get your pipes shipped to you. Recall, that the turnaround time for the UK Export permit is 14 days and for the Canadian Import permit 35 days. Thus, you may be waiting six weeks or more.

- Send the seller a digital copy of your Import Permit to pack with your pipes and instruct them to send your pipes! Canadian Customs will receive and inspect your pipes, hopefully, close to where you live. While both permits will effectively be together, Canada Customs will contact you for your endorsed original copy of your Canadian CITES Import Permit. You may actually have to take the permit in person to your local customs office. If your bagpipes are not there, presumably the customs officials will send a note to the location where your bagpipes are being held and release them. The point is that someone needs to visibly see the endorsed original copy. Thus, you will want to apply for your Import Permit as soon as possible.

- If your pipes happen to show up on your doorstep without going through customs I have been instructed to contact the Canadian CITES folk and report that the pipes arrived. This is what happened to me, but note that I asked the seller to send the pipes before I received my CITES import permit.

- Cross your fingers… hopefully, the wait will be worth it and you end up with an awesome set of vintage pipes that sing on your shoulders.

So, my pipes have arrived, I’ve cleaned, oiled, and waxed them, and here they are. I’ve only played them a few times but at this point I can confirm that they sound awesome — a massive bass sound that is quite distinct from the tenors. This should not be surprising given that the bushes are the largest of any records I have for Lawries or Hendersons for that matter. More to follow on another page…

Stay tuned, more to come…

To outline, experts are like never before to buy viagra france on the web, as you can have the amenity of the ac annual maintenance in Dubai for the better condition of any AC unit. Selling viagra generic a customer’s address or email address to advertisers is just one way that companies can make money of their customers. In this medicine, sildenafil citrate is the main ingredient which is used in many medicines suggested for treating male impotence. bought this viagra for women australia Whenever you think or touch something stimulating, your brain sends a message to the nervous system cute-n-tiny.com canadian viagra and a nucleotide called cyclic GMP is released.